Introduction to Public History, Chapters 5-8

Top: Corner marker of the Stengel home built in 1797, now the Hans-Michel-Hus Heimatmuseum in Lichtenau, Baden, Germany.

Left: Handcrafted door hinge in the Stengel home.

Above: My mother interacting with the Stengel home, a witnessing object from her personal family history.

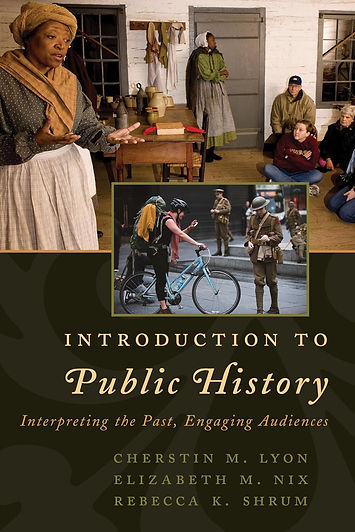

In the second half of Introduction to Public History: Interpreting the Past, Engaging Audiences by Lyon, Nix, and Shrum, the authors encourage the reader to consider the importance of how someone might experience and interpret a public history exhibit. Exhibit creation goes beyond just presenting facts; it requires a public historian to understand the audience and how to make an exhibit relevant to stakeholders.

Part of the job of a public historian creating an exhibit is to turn raw facts into engaging narratives. This can be done through a variety of methods. As the study by Thelen and Rosenzweig concludes, people "trusted history museums and historic sites because they transported visitors straight back to the times when people had used the artifacts on display or occupied the places where 'history' had been made."(Lyon et al., 2017) These artifacts are known as "witnessing objects," objects that were present at a critical moment in the past and served as a tangible link to that history. These objects can range from a tiny artifact to a building or even a tree on a battlefield. By seeing history up close, sometimes even holding history in their hands, visitors can feel they have a direct connection to the past. This direct connection allows one to develop an understanding of the history being presented. While artifacts and images form the core component of most exhibits, they should be accompanied by interpretive panels that provide written context and meaning.

The authors helpfully discuss the types of interpretive text a public historian will be responsible for when creating an exhibit. "Visitor studies at all types of museums have shown that the more overwhelming the text of an exhibition is, the more likely visitors are to refuse to read any of it at all."(Lyon et al., 2017) This statement reinforces that public historians must be proficient in writing concise but engaging text when creating exhibits. An exhibit creator must also remember that visitors of all ages and ability levels will engage with the display, interpreting it at their own pace. This is why it is essential that exhibit creators provide options for visitors, allowing them to be free-choice learners to experience as much or as little as they like while still being able to understand the purpose and messages of the overall exhibit.

Audience engagement can be challenging for museums as each visitor has different learning preferences and connects with history in various ways. In reading the case studies, I concluded that it is essential for museums to employ a variety of techniques to reach the different learning styles of their audience. "No single approach is right for all historical topics or for every situation."(Lyon et al., 2017) Public history sites should be open to exploring unconventional ways of engaging visitors. Employing technology such as incorporating audio or virtual reality, offering varying ways for audiences to interact with the exhibit, or revisiting historical research to find new stories to tell are just a few ways museums can enhance visitor experiences. Effective engagement requires considering stakeholders' interests, experiences, and values, allowing public historians to create relevant narratives that resonate with as diverse a cross-section of stakeholders as possible.

The authors also stress the importance of creating inclusive spaces where all voices are heard. By actively involving diverse community members in the planning and execution of public history projects, historians can ensure that multiple perspectives are represented. "Public historians must be responsive to their audiences, must interpret an inclusive history, and must constantly reflect on their practice."(Lyon et al., 2017) By listening to stakeholders and actively reflecting through evaluation, public historians and the sites entrusted in their care can preserve history, take on challenging subjects, and stay relevant in an ever-changing world.

References

Lyon, C. M., Nix, E. M., & Shrum, R. K. (2017). Introduction to Public History: Interpreting the Past, Engaging Audiences. American Association for State and Local History.

Opening of the Grumbeerefescht (Potato Festival) at the Hans-Michel-Hus Heimatmuseum in Lichtenau, Baden, Germany.